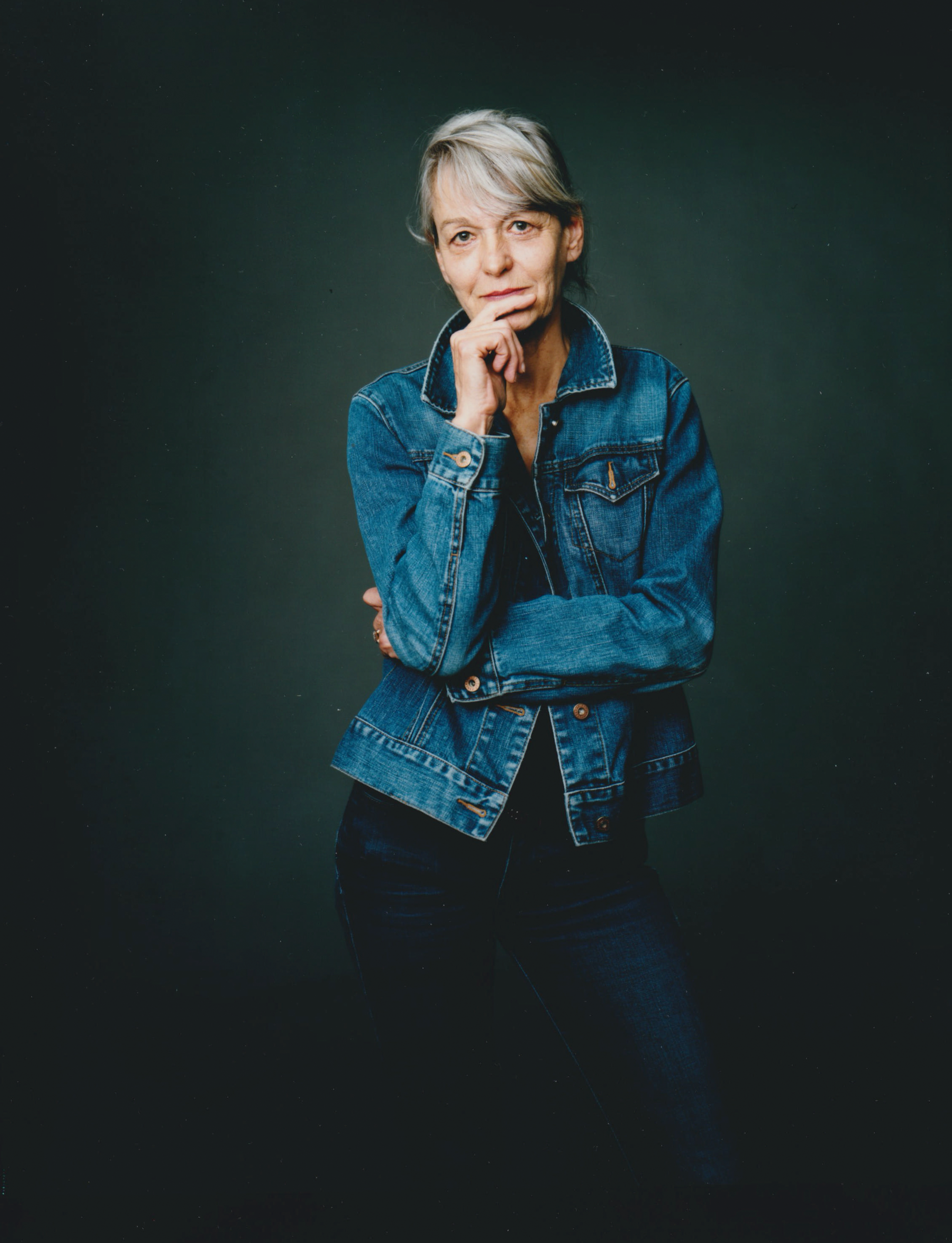

All rights reserved: Agnès Godard

Agnès Godard (2023)

Bodies as Landscapes

In May 1982, Wim Wenders set up a 16mm camera in room 666 of the Hôtel Martinez on the Croisette and asked filmmakers attending the 35th Cannes Film Festival (including Antonioni, Jean-Luc Godard, Fassbinder and Spielberg) to talk about the future of cinema. Unbeknownst to them, it was already right there in the room – only, it was behind the camera. For there stood the French cinematographer Agnès Godard, whom we are honoring with a tribute.

Godard was born in 1951 in Dun-sur-Auron, a small town southwest of the Val de Loire. She studied in Paris in the 1970s and worked as assistant to cinematographer Henri Alekan, with whom Wenders shot ›The State of Things‹ in the spring of 1981. Godard then assisted Robby Müller on ›Paris, Texas‹ (1984), and again Alekan on ›The Sky Over Berlin‹ (1987). By a happy coincidence, Wenders’ assistant director was the Parisian Claire Denis, whom Godard already knew through a mutual friend – thus was planted the seed of one of the most fruitful working relationships of contemporary French cinema.

The serial killer film ›I Can’t Sleep‹ (1994) and the sibling drama ›Nénette and Boni‹ (1996), both bathed in vivid contrasts of blue and red, kicked off a collaboration that to date stretches across nine films. ›Beau travail‹ (1999) and the vampire horror ›Trouble Every Day‹ (2001) were followed by the lyrical-romantic dramas ›Friday Night‹ (2002), ›L’intrus‹ (2004) and ›35 Shots of Rum‹ (2008), which alternated between urban and rural settings, breaking new visual ground time and again. These are films that cannot be reduced to one uniform style: the dark nightmare of ›Bastards‹ (2013) was followed by literal light, in the form of the brighter ›Let the Sunshine In‹ (2017). On the whole, however, the films she made with Denis are more stylized, whereas for another pivotal film, Erick Zonka’s ›The Dreamed Life of Angels‹ (1998), Godard crafted a radical vérité style with a handheld camera. Then, work in television preceded collaborations with women directors such as Noémie Lvovsky or Catherine Corsini.

Godard shot some of her most important films with homosexual directors. It is striking how vividly these works highlight the motif that is perhaps most essential in her style: her camera’s treatment of the human body. In both Jacques Nolot’s ›Hinterland‹ (1998) and Sébastien Lifshitz’s ›Wild Side‹ (2004), the dying body of an elderly mother being washed by a relative is juxtaposed with the merging bodies of younger people (in a bar, on the dance floor, in loving embrace). And when physicality is represented in the more recent film ›Salvation Army‹ (2013) by the openly gay Moroccan Abdellah Taïa, who lives in exile in Paris, the connotations are, of course, again wholly different.

Currently, one of her most important collaborations is with director Ursula Meier, on the films ›Home‹ (2008), ›Sister‹ (2012) and ›The Line‹ (2022). These films embody, among other things, the transition from analog film to digital images – and here, too, Godard is lending her hand to writing the future of cinema.